- 1.3

Eurodesign, European institutions and policies

What makes Europlanning "special"?

The term “europlanning” identifies the process and technique of preparing projects financed through European funds. Why does this term exist and what makes European projects different from other types of projects?

First of all, it should be specified that the process and technique of elaborating projects financed by other major international players are not structurally different from those used in europlanning. Most of the tips and principles for developing a good project apply regardless of the funding agency.

However, the architecture and mode of operation of community funds are indeed particular and have warranted the development of special studies and tools over the years, such as and example of this Guide. This ultimately depends: 1) by the architecture and mode of operation of the European Union, which are particular and in many ways unique (as already previously observed); 2) from the fact that projects are an application of policies (as explained in the very first chapter); which are in turn the result of institutional arrangements. It follows that the architecture of European projects is also the product of a unique institutional arrangement.

In this chapter and in the following one , we will trace the path from the institutional and political set-up of the EU to the definition of European projects, showing their relevance to europlanning activities.

The foundations of the EU's institutional set-up.

The current institutional set-up of the EU is the result of three major approaches, or schools of thought, that have alternated and overlapped in defining the process of European construction:

- The intergovernmental approach: the European Union came into being by the will of the member states, which are the holders of sovereignty and ultimately the “shareholders” (with decision-making rights) of the European Union and all its structures. This approach is visible in the leading role exercised by the European Council in key decisions affecting the EU;

- The federalist approach: the European Union is much more than a “union of sovereign states,” but possesses a “soul” and a principle of citizenship, which needs to be brought out; transforming the EU into a federal state with continental reach, endowed with the powers and sovereignty necessary to stably and effectively meet major global challenges, especially in terms of peace and development. This approach is visible in the role exercised by the European Parliament in decisions affecting the EU. Parliament is a body elected by universal European suffrage, the bearer of the principle of democratic legitimacy and European citizenship;

- The functionalist approach: the European Union was born and developed to address common problems and by giving itself common tools. The combination of these tools and the need to make them work effectively will actually lead to increasing integration and a gradual increase in the competencies of community institutions. This approach is visible in many EU policy areas. For example, the introduction of the euro, the bearer of important economic benefits , opens the debate about (and in part, creates the need for) further progress in European integration (European fiscal policy, Eurobonds, etc.).

Each of these approaches has its own logic, different and distinct from the others. The alternation and coexistence of different logics in the process of European construction has led to a peculiar division of competencies between EU institutions and member states. The effects of this division of competencies are also reflected in Europrojecting: for example, they underlie the existence of different and specific operating mechanisms between projects intended for the territories of member states (Structural Funds) and those intended for the Union as a whole (directly managed European programs).

From EU treaties to EU projects

Although there are, as we have seen, different approaches and visions on the nature and future of the European Union, it is clear that the EU was born of a specific will of the member states and that it is also (though not only) intergovernmental in nature.

In this context, treaties between member states acquire structuring importance for the whole process of community building. In particular-a very important aspect for europlanning-the treaties define the areas of competence of the EU institutions and how they can make decisions.

Based on this “perimeter” defined by the treaties, the EU institutions develop strategies and policies. European projects are-following this-the operational application of these strategies and policies.

Treaties have a long history and have been revisited several times: Treaty of Rome (1957), Treaty of Brussels (1967), Single Act (1986), Treaty of Maastricht (1992), Treaty of Amsterdam (1997), Treaty of Nice (2001), Treaty of Lisbon (2007). The latter is known as the “TFEU,” or “Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.”

The areas of intervention of community institutions are defined by the TFEU as follows:

- Exclusive areas of expertise (Art.3 TFEU): customs union, competition, euro, marine resources and trade policy; and, when provided or necessary, international agreements;

- Shared areas of expertise (Art.4 TFEU): internal market, social policy, economic, social and territorial cohesion, agriculture and fisheries, environment, consumers, transport, trans-European networks, energy, freedom, security and justice, and public health; plus space, development cooperation and humanitarian aid (areas in which member states can conduct autonomous policies);

- Complementary areas of expertise (Art.6 TFEU): health, industry, culture, tourism, education, training, youth and sports, civil defense and administrative cooperation.

This list provokes three important reflections: 1) the areas of intervention are indeed many and very broad; 2) In them it is possible to recognize the areas of intervention of many European funds and programs; 3) the subdivision is not simple because it is organized into different and multifaceted levels of competence (vis-à-vis member states). The principle of subsidiarity provides the key to defining the respective competences: the Union’s intervention can exist in cases where it enables common objectives to be achieved more fully and effectively than what can be achieved by the member states.

These areas should be combined with the modes of intervention available to community institutions. In fact, the EU is not a state, and compared to a state it has a more limited range of forms of intervention at its disposal. For example, it has no major services and infrastructure to manage (e.g., a school, health, welfare, safety, road, and rail system…), no territory over which to exercise control or authority, and no participation in public or quasi-public business activities. The EU can exercise its functions under the treaties primarily through:

- Legislative activity , consisting of regulations (acts that are directly binding throughout the EU), directives (acts that require implementation by member states), decisions (acts that are directly binding on specific addressees), recommendations and opinions (non-binding acts), conclusions and resolutions of the Council (non-legal documents of strategic importance);

- The management of the euro and monetary policy by the European Central Bank (for its member countries);

- Various forms of financial support, including, for example, direct grants, trust and guarantee funds, and “blending,” or synergy activities with other forms of public or private financing;

- Through projects, that is, calls (calls for proposals), grants, subsidies and tenders (for the provision of services, materials or works).

Thus, it is clear that projects are a key tool to enable community institutions to carry out their functions in the various areas of intervention under the treaties. In fact, the overwhelming share of the community budget is devoted to financing the funds and programs from which European projects arise.

Since European projects constitute “action” on the part of EU institutions, the aforementioned principle of subsidiarity applies to them: associated with European projects are the concept of “EU added value” and a fundamental distinction in terms of scope of reference (“EU-wide” projects financed by EU programs, “local-wide” projects financed by Structural Funds, co-managed and co-participated by member states).

The reference documents

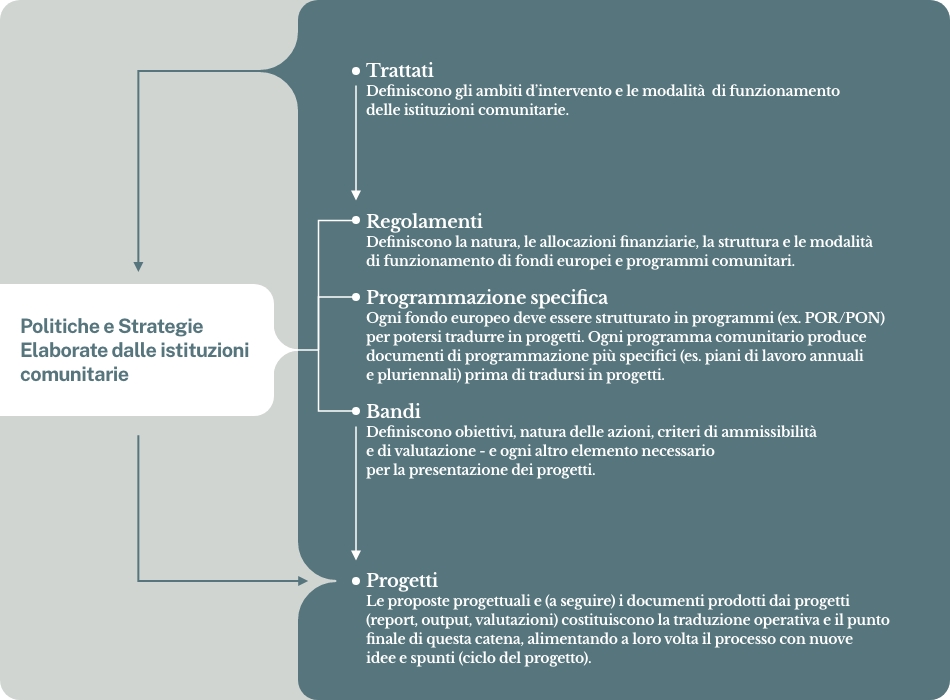

It is possible to understand the “thread of logic” leading from the architecture of EU institutions to European projects by briefly going through the main reference documents, i.e., the main “formal steps” leading to European projects. These “stages” constitute the formalization of the policy and strategy-making process carried out by the European Union.

Since projects are an (important) form of policy implementation, it is very important to know (and recognize) the European policies in the policy areas in which you work, and to refer to them within your projects (the same applies to national and regional policies, in the case of structural funds). Having a clear understanding of what policy objective the project is intended to contribute to, and demonstrating an effective impact in this regard, is one of the most important aspects of designing a successful proposal.

To be able to do this, it is necessary to know how to retrace the path through policies and strategies that lead to the establishment of a regulation, a program, and finally a notice. The NEXT CHAPTER aims to illustrate this pathway for the main categories of community funds and programs.

Institutions of reference

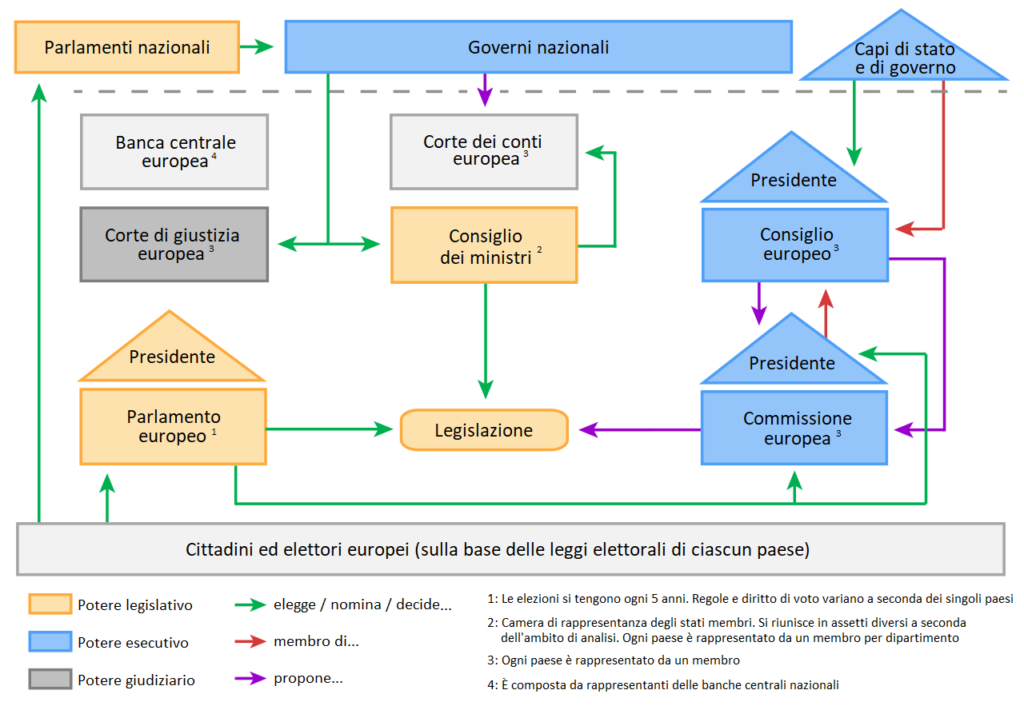

For better understanding, we provide below a useful chart (taken from here) which briefly illustrates the functioning of the European institutions.

The main ones are:

- The European Parliament : is, together with the EU Council, the legislative body of the Union. He is elected by universal suffrage in all member states. It has legislative power , budgetary power e power of control . It is organized into 26 thematic commissions and in 7 Political Groups . It has a research service that produces analyses useful for understanding European policies;

- The European Commission : is (by far) the main interlocutor for those involved in europlanning, because it has an operational role in the definition and management of EU funds and programs. Contributes to, develops, proposes and implements EU strategies, policies and legislation. It has political leadership provided by the College of Commissioners . It is organized into DGs, Executive Agencies and Services (information also here ), Representations (in member states) and Delegations (in third countries);

- The European Council and the EU Council: are often generically identified as the “ Council “, share the same seat, the same website, and are both emanations of national governments, but actually have different functions. The EU Council (or Council of Ministers) is together with the Parliament, the legislative body of the EU: it is, so to speak, its representative component of the states, where the Parliament represents the citizens instead. It consists of ministers and representatives of member states in the different thematic areas (so it meets in different compositions depending on the topic). The European Council instead brings together heads of state and government to set overall EU priorities and directions.

Reference policies

Policies and strategies in the various policy areas of the European Union represent a constantly changing and evolving terrain. There are many sources and many channels through which to keep up to date:

- The site that collects the strategic priorities of the European Commission , which regularly recur in all major policy, strategic and also operational documents (programs and calls). Those related to the 2019-2024 period are: The European “Green Deal” , A Europe Ready for the Digital Age , An economy that serves people , A stronger Europe in the world , Promotion of the European “way of life” e New momentum for European democracy . Similar priorities are reflected in the Structural Funds programming. ( we have discussed them here ). Each of these six priorities is further separated into more specific areas, actions and “policy areas” (accessible from the respective links);

- The reference site (Eur-Lex) which brings together for each of the thematic areas EU legislation and legal acts (which are the most “official” way in which EU competencies are manifested);

- The EU website which collects information on the main thematic areas of intervention (which in turn links to the main reference sites in the different subjects);

- The websites of the individual Directorates General of the European Commission: they are the ones that, in the different thematic areas, develop, propose and implement EU strategies, policies, legislation. It is therefore advisable to consult the website of the relevant DG when preparing a European project (some examples: DG EAC , DG EMPL , DG ENV , DG REGIO , DG HOME , DG SEA , DG AGRI …);

- The websites of the European Parliament (pages on current events , priorities e research service ) and Council (pages on topics , policies , research e publications ). Together with the Commission, both represent active and informed parties to the strategic and policy-making process in the EU;

- The basic reference documents for writing a project (regulations, work programs and calls for proposals). The services of the European Commission and Managing Authorities are also required to maintain alignment with existing policies and strategies and reflect them in the documents they prepare (normally in their introductory part);

- The prospectus of the Europlanning Guide, which devotes specific space and links to easily find the strategic and outline elements on each fund and program to better inform project writing.

Genesis and relevance of the community budget

The EU budget is another typical element of the complex institutional architecture of the European Union. It has a definite “structuring” impact on European funds and programs. The community budget and its definition process (which we have explored in depth here ) do not follow a single path, however, but are made up of various components:

- The financial perimeter in which community funds, programs and institutions can act, given by the decision on the Own Resources . A special legislative procedure follows ( ex Art. 311 TFEU ), in which the decision rests with the Council with consultation of the European Parliament;

- The structure of the community budget (with respective allocations to funds and programs) for a seven-year period, given by the decision on the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). A special legislative procedure follows ( ex Art. 312 TFEU ), in which the decision rests with the Council with the approval of Parliament;

- The annual executive framework of the EU budget, given by the decision on the annual budget of the EU . A special legislative procedure follows ( formerly Art. 314 TFEU ) which provides for symmetrical powers of the Council and Parliament;

- The framework of specifics of individual EU funds and programs, which make up the bulk of the EU budget. The Regulations constitute the “rules of the game” in the implementation of the EU budget and (more specifically) of all Europrojecting activity. They follow the ordinary legislative procedure ( ex Art. 294 TFEU ) which provides for 3 “readings” by the Council and the European Parliament, with “conciliation” and “trilogue” procedures at the stages when agreement between the two institutions is most urgent and necessary. The legislative history of each fund and program can be found under “process” in our prospectus .

It is very important to follow the evolution of each of these processes, because it is on them that the structure, financial volumes, and rules for carrying out europlanning activities throughout a seven-year period depend. Follow her closely (also with the help of our Guide ) also allows one to learn about the political genesis of the various programs and consequently meet the expectations that the community institutions had set for the projects to be funded.

Community budget structure

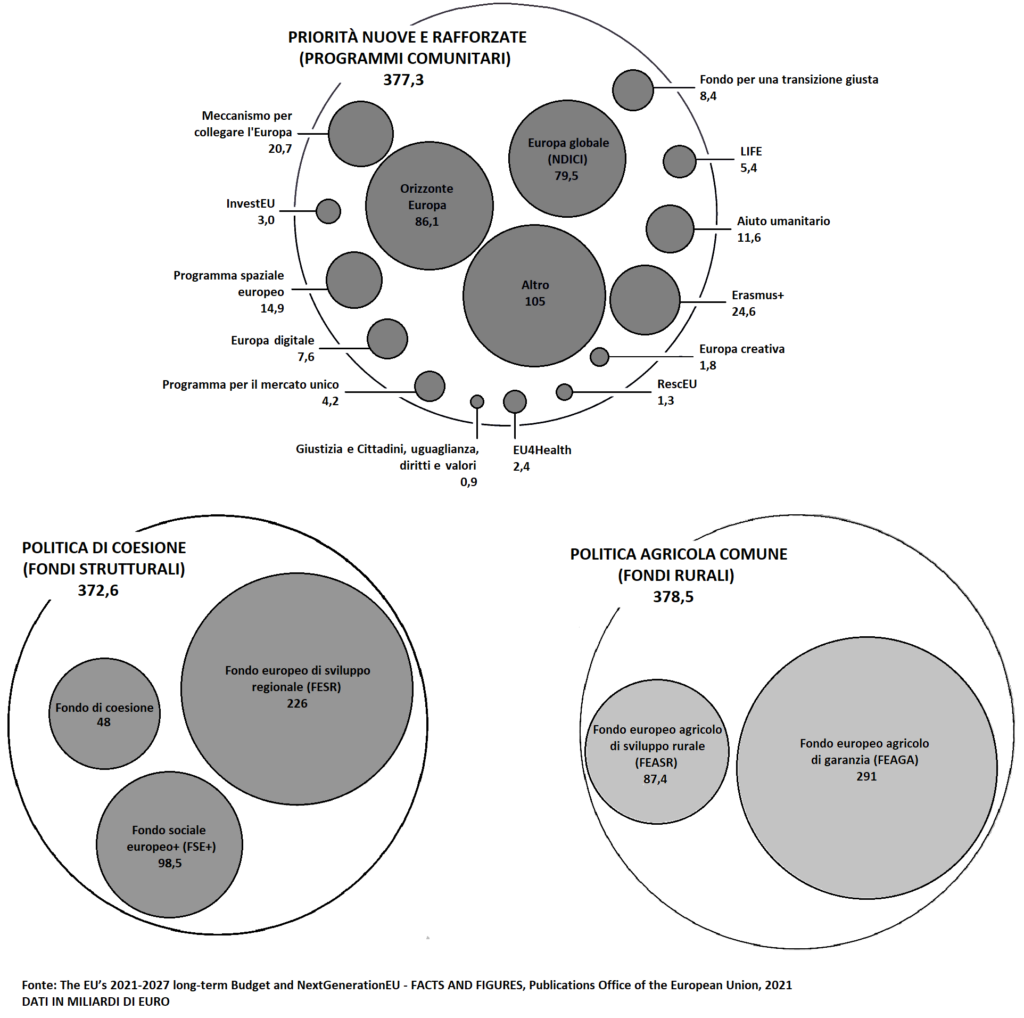

There are a total of six headings in the community budget (plus a “minor” one related to the operation of community institutions). They are taken verbatim within our prospectus , to further emphasize the close link between community budgets and European projects.

The chart below provides a visual summary of the structure of the community budget . It is not organized by budget headings (however, easily accessible from the prospectus ), but by fund category. The size of the circles is proportional and shows how the Structural Funds, rural funds and community program funding each absorb a similar share of the community budget; and their internal divisions.

To these amounts must be added the “special” allocation (outside the community budget proper), consisting of the Recovery and Resilience Facility. It has a total amount of 806.9 billion, broken down into 338 billion in grants, 385.8 billion in loans and 83.1 billion in “extra” contributions to some community programs.

Of course, all data refer to the entire European Union. For an estimate of the funds allocated to Italy you can refer to one of our post dedicated to .

From policies to projects, at a glance

As part of their functions, community institutions produce and implement numerous policies and strategies, in each of the areas of intervention provided by the Treaties.

This strategic and policy activity takes place upstream and in parallel to the legislative activity of the European Union; and is (at the same time) its continuation in operational terms.

Legislative activity translates (particularly, as far as Europrojecting is concerned) into a seven-year Financial Framework, an annual budget, and Regulations that regulate the execution of EU funds and programs-and, consequently, the ways and timing in which European projects are designed and implemented.

Policies and strategies continue to evolve throughout a seven-year term. They continue to identify and order EU priorities in response to existing and emerging needs. In some cases, these reflections produce new funding lines that are “parallel” or “experimental” to those already provided for in the Seven-Year Financial Framework, for which the Framework itself provides provision and reserve items.

The execution of community funds and programs in turn involves subsequent programming activity, which is necessary to generate calls and projects from the general lines given by community policies, strategies and regulations. This “second programming” takes different forms depending on the type of fund or program, producing as appropriate:

- Work Plans or Work Plans ( WP ), for directly managed thematic programs;

- Partnership Agreements ( PA ), Regional and National Operational Programs ( ROP / PON ), Rural Development Programs ( RDP ) and Territorial Cooperation programs ( PCT ), for Structural and Rural Funds;

- Multi-year indicative programs (MIPs) ( 1 | 2 | 3 ), Annual Action Plans ( AAP ), Action Documents ( AD ) and Humanitarian Indicative Plans ( HIP ), for External Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid programs (the acronyms echo the more widely used English definition).

These documents will be taken up in the next next chapter . The analysis of these documents, of the strategies from which they derive and refer to, and of the debate developed by the EU institutions in the various thematic areas is very important for the activity of Europlanning, because it enables the development of European projects in line with the objectives of those who fund them.

Funds, programs and tools

Europlanning activities are carried out from funds, programs and instruments, governed by specific regulations, which form their legislative basis. Funds, programs, and instruments produce intermediate planning documents (listed above) and the calls from which europlanning activity flows. However, the difference between these three categories is not always very clear, and the related concepts are frequently overlapped. However, an indicative distinction can be drawn:

- The concept of “fund” recalls the principle of “dedicated amount” (to something and someone) and the idea of complementarity between different financial sources. Thus, “funds” are defined as funding lines that involve shared management between EU institutions and member states; which frequently contribute a share of national co-financing to the fund.Fund examples: European Social Fund, European Regional Development Fund, Asylum Migration and Integration Fund, European Defense Fund, etc.

- The concept of “program” recalls the ideas of “intention” and “execution.” Thus, “programs” are defined as funding lines that provide for direct management by the departments of the European Commission and its Implementing Agencies.Program examples.: Horizon Europe, Erasmus+, Creative Europe, LIFE, etc.

- The concept of “tool” or “device” invokes the idea of something more complex and that “serves to” do something else. Thus, “instruments” or “devices” are defined as funding lines that provide a mix of solutions, such as a mix of funds, programs, management modes, and forms of support (financial and non-financial).Examples of instrument or device.: Recovery and Resilience Instrument, Foreign Policy Instrument, Connecting Europe Facility, etc.

We propose here a more in-depth discussion of the concepts of direct, indirect and concurrent management.